Miles Away: The Hookses with Uncle John

The following is a reflection from Todd Shy who served as a study assistant to John Stott from 1988 to 1992.

On the five-hour drive from London to the far reaches of southwestern Wales, the last stop for groceries and hardware supplies was Haverfordwest, a small city circled by a winding one-way street that sloped beside an industrial canal. From there the back road to the coast and to the village of Dale reached into open farmland. High hedgerows framed the unmarked lanes that occasionally broke from the main road. From an airplane, the landscape was an irregular lush patchwork haphazardly seamed with old stone walls and the hedgerows that made the scenery hard to take in from the car.

The final road to Dale was a wending lane so narrow that for several miles there were little knots in the road (lay-byes) that let an approaching car pull over so the other could pass. Just over the hedge line, you could glimpse the sprawling fields and the gorse bushes with burry, pollen-colored blooms, and then eventually, when the road turned away, a beautiful bay filled with windsurfers and, farther out, oil tankers leaving the refineries at Milford Haven. Once, when I went out in a terrific storm to pick up a visitor for John Stott from the train station, I thought we might get stranded between these hedgerows. It was pouring rain when I left, and when we returned the lane had flooded where it dipped, and I got out to wade into the pooled water to decide whether we could even pass. It was still raining hard, and I thought, if we don’t try now, it will only get worse, and what would we do then? Gunning John’s Volkswagen, I pushed ahead. The gathered water pulled hard at the car, throwing beautiful, symmetrical, Mercury wings to each side. We made it through to higher ground. All that time, the visitor, one of the many doctoral students John’s Trust supported financially, went on telling me about his research on Matteo Ricci. I leaned to the wheel like the cab drivers in London pretending to listen. In Dale itself, the swollen sea had already battered through the village wall, and people were out in their rain slickers stacking bags of sand at the breach.

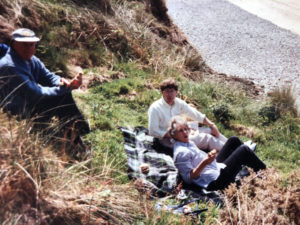

Another time, John, Frances and I participated in an outdoor worship service at a nearby farm. It was Harvest Sunday, and a small group of us met together in someone’s barn, the big doors pushed wide. The local vicar prayed for the New Potatoes. We sang. The inland view from where we stood sloped dramatically down then back up again, and the hillside in either direction was the lush rural green you associate with Ireland and Scotland, and, for me now, Pembrokeshire in Wales, where John Stott bought a derelict farm in the 50’s and refurbished it over the years as a writing retreat: The Hookses. When I was his study assistant, we went four times a year for three-week work stretches. And it’s true that for this twenty-two-year-old who had grown up in the Appalachian hills and been invited, with what seemed at the time an extraordinary act of providence, to work with one of his own college heroes, London, for me, was the more formative sphere. When I think of my time as John’s study assistant, I think of London and the world it opened up, but when I think of Uncle John—my time with him—I think most often of that reclaimed farm and our rituals there. It was where my job even started. When I flew over from the States to start this improbable adventure, John was already at the Hookses working, and Frances and I drove there to meet him.

Another time, John, Frances and I participated in an outdoor worship service at a nearby farm. It was Harvest Sunday, and a small group of us met together in someone’s barn, the big doors pushed wide. The local vicar prayed for the New Potatoes. We sang. The inland view from where we stood sloped dramatically down then back up again, and the hillside in either direction was the lush rural green you associate with Ireland and Scotland, and, for me now, Pembrokeshire in Wales, where John Stott bought a derelict farm in the 50’s and refurbished it over the years as a writing retreat: The Hookses. When I was his study assistant, we went four times a year for three-week work stretches. And it’s true that for this twenty-two-year-old who had grown up in the Appalachian hills and been invited, with what seemed at the time an extraordinary act of providence, to work with one of his own college heroes, London, for me, was the more formative sphere. When I think of my time as John’s study assistant, I think of London and the world it opened up, but when I think of Uncle John—my time with him—I think most often of that reclaimed farm and our rituals there. It was where my job even started. When I flew over from the States to start this improbable adventure, John was already at the Hookses working, and Frances and I drove there to meet him.

That narrow road beyond Haverfordwest opened to the bay, and then the single lane looped past the sea wall and the post office that doubled as a small general store (you’d go in, and there would be a small dish of quail eggs on the counter, beside some local potatoes), past a bed and breakfast and a line of stucco homes, and finally the village church with its little graveyard, and, just beyond, a true medieval castle, whose reclusive duchess still owned most of the land you could see, but not John’s farm. We turned up a hill between more hedgerows. At the crest, I had to get out to open the wide farm gate and then close it again behind the car. We were on a plateau now, driving on the big cement panels of a World War Two airfield. The strip was derelict, cracked with weeds and tufts of grass, and yet it wasn’t hard to imagine picking up speed and heading straight for the cliff line, as the pilots would have done for a night mission to France. Ahead was the ocean’s near horizon, and all around the airfield, on the neighboring farm, 700 or so sheep would work their way daily around the property, crossing the runway and circling down by the fence that separated John’s small retreat from the duchess’s rented fields. Beyond the cliff line was a second headland, and beyond that, Skomer Island, where we sometimes took visitors to bird watch, and more distant but still visible, uninhabited Skokholm Island, which was a breeding ground for gannets. At the right time of year, Skokholm appeared to the naked eye to have suddenly whitened, and through binoculars you could make out the shiver of the thousands and thousands of mating birds.

It was a neat optical trick that the Hookses wasn’t visible until you turned down the driveway. The road dropped dramatically into a little scoop of coastline, and on the slant stood a white farmhouse without shudders, and several stone outbuildings that descended towards a kidney-shaped pond. By the pond was the hermitage where John Stott slept and worked, looking out over the bay. It was a breathtaking spot. A creek dribbled through the property, then dropped fast to the ocean. John had built a small sluice to ration the flow into the pond. All around, gorse bushes spotted the headland, and the sheep, grazing among them, would leave fists of wool on the thorns. Out in the bay, and beyond in the open Atlantic, the lapping waves played in the sun that day like so many breaching dolphins.

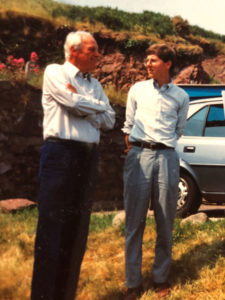

When we arrived that first time, Frances told me to ring the ship’s bell by the farmhouse door, which was how we signaled John for meals. Presently the great man came up the hill, wearing the outfit I would see him in every single day we were ever at the Hookses: dark corduroys, a zip-up sheepskin sweater, a quilted outer vest. I had flown over in August to interview, so we’d met and spent five days together back in London. Now he was smiling as he approached us, his narrow eyes disappearing, broken capillaries like tiny cuts on his cheeks, his white hair tousled by the breeze from the bay. He hugged Frances first then he welcomed me with a hug. I don’t remember whether it was in that moment or very soon after that he dubbed me “the young man.” (It was the wife on the neighboring farm who later dubbed me, John’s minder.)

While Frances unpacked and worked on lunch, John showed me around the property. He was on a camping trip in the early Fifties when he discovered the place, he explained. It was in terrible shape, but he could see the structure was solid. He bought it with royalties from his first book and improved it with other royalties over the years. It still didn’t have electricity, but originally it didn’t even have gas. In one of the outbuildings, he showed me the Honda generator that was used only to power Frances’ computer. Other outbuildings were spare, outfitted with small desks and twin beds. Finally, John showed me the hermitage where he slept and worked. The view from his desk was remarkable: the curve of the coastline falling toward the bay and then the Atlantic itself, which I grew up viewing from the faraway other side. Behind John’s desk were several cases of reference books. All the Church Fathers were here. All of Calvin. Flanking the study, his bedroom was a tiny annex behind a shoe-store curtain.

While Frances unpacked and worked on lunch, John showed me around the property. He was on a camping trip in the early Fifties when he discovered the place, he explained. It was in terrible shape, but he could see the structure was solid. He bought it with royalties from his first book and improved it with other royalties over the years. It still didn’t have electricity, but originally it didn’t even have gas. In one of the outbuildings, he showed me the Honda generator that was used only to power Frances’ computer. Other outbuildings were spare, outfitted with small desks and twin beds. Finally, John showed me the hermitage where he slept and worked. The view from his desk was remarkable: the curve of the coastline falling toward the bay and then the Atlantic itself, which I grew up viewing from the faraway other side. Behind John’s desk were several cases of reference books. All the Church Fathers were here. All of Calvin. Flanking the study, his bedroom was a tiny annex behind a shoe-store curtain.

We had lunch that day out on the terrace, and then we settled into our routine. The rhythm of all Hookses days was unchanging. I can describe that first week and be describing my fifteen or so visits in the subsequent four years. Every moment was taken captive, as the Apostle Paul suggested. Every task was part of an order. John rose just before five a.m., greeting by name each person of the Holy Trinity. Then he did a few simple calisthenics, showered, shaved and had his quiet time using Robert Murray McCheyne’s Bible reading calendar. By six-thirty he was at his desk, working. Meanwhile, it was customary for the study assistant to wake Frances up with a cup of tea. There was no electricity. I rose early and put the kettle on the coal-burning stove, and while the slow water boiled, I riddled the night’s ashes, emptied the pan, shoveled in more coal, and read my Bible. At six-thirty I took Frances her tea and had a quiet time in my room. At the peak of summer, or even early September, light was abundant, but at other times of year, I had to light the gas lamps to read. Inside those glass globes, a pipe blew loud propane into a pouch of starched netting, and you held the match just outside until it caught, bursting white like the strips of magnesium we lit in high school. One time, at six in the morning, the match head broke off as I struck it, and it flew into my eye. When I went to wake her for help, Frances rushed out of bed in a Victorian nightgown to flush the cold cinder free.

At 7:48 I always walked down to the hermitage and at ten minutes to eight precisely knocked quietly on John’s door. He called me in. While Frances prepared a simple breakfast in the main house, John and I knelt on the floor of his study to pray. We each took a turn, John with his face in his hands, slowly, deliberately entering the presence of God. I had to learn to do the same. The American evangelicals who nurtured me bounded into God’s presence, all of us speaking in the same voice with which we answered the phone: “Lord, we come before you….” “Father God, we just ask you….” “Almighty God, there is nothing you don’t know and nothing you need from us….” Praying with John—always on our knees—I had to adjust to taking my time, to shifting registers. With his face literally pressed to his hands, John eased into prayer, almost muttering, and always beginning, “Our Father,” exactly as Jesus had taught. How still we remained on our knees as we prayed. Even in my memory I hear the gears of the carriage clock on his desk flicking their insect wings, the only other noise.

At eight, breakfast would be waiting on the table in the main house. We each had muesli and one piece of toast with butter and marmalade. Toast racks to cool the toast were something I’d never seen or even heard of before. (To this day, decades removed and back in the States, I let my toast cool before I butter it.) We had coffee together but drank it fast. I was on cleanup duty for breakfast. By eight-thirty we were all at our various spots working.

For the rest of the day, John would write at his desk, while in her adjacent office Frances would type and print portions of his manuscripts for me to proofread in the main house. Part of what pushed John forward, I suspect, and made him so productive, was the need, in the back of his mind, to keep us busy too. He gave me various other tasks whenever we were at the Hookses, some of them long-term work like reading back over an earlier edition of a book and noting things to update. But for that initial fortnight, I had a simple, grand assignment to read as many of John’s books as I could in the time we were there. He wanted me, he explained, to know his mind. I’d probably read five or six of his books already—he was iconic in my evangelical circles at the University of Virginia—but John had written more than thirty, a few of them out of print, some never in print in America. I began at the beginning and worked forward chronologically. It was a thrill to talk to him about his oeuvre over meals.

If the weather was nice, we ate a simple lunch out on the terrace, and John would tell us how the morning’s work went. “I was helped” he would say when he was productive. He was almost always helped. Sometimes he talked us through a dilemma or told us what various commentators had observed of a certain biblical passage. Writing for evangelicals, John wrestled with liberal and academic commentaries on whatever he was writing, doing the hard work on our behalf so we could understand the biblical view more deeply. Always after lunch he would go downhill for his nap, what he called his HHH (horizontal half hour), and then at 2:00 he and I did a half hour or sometimes, if the weather was nice, an hour of chores together. Sometimes this involved regular maintenance of the property, sometimes we advanced a bigger project, like a stone waterfall we made in the stream, or the trellis we built on one of the outbuildings. One time, in a rare quixotic quest, John had us drain and then clean out the artificial pond. When the water shallowed out, he and I waded into the muck in Wellington boots and started shoveling out the last layer of mud, which turned out to be full of eels. They were everywhere in that remnant slime, and as I grubbed at them with big-gloved hands, tossing them in buckets, jumping away the way you do from snakes, John laughed hard at my antics. I didn’t love manual work, I didn’t especially love the outdoors, but what did I care? I was working with John Stott. Whatever needed to be done felt like a privilege. It took all week to scrape that concrete bottom clean, and when we released the sluice again, and it filled, we put in water lilies and goldfish and a perimeter of pointed rocks to keep the herons away from the goldfish, but it wasn’t long before the pond was as overgrown and murky as before. John had the builder come out, and when he pressed him for a long-term solution, the builder replied with patient bewilderment, “A pond’s a pond, John.”

Clearly John loved this afternoon labor (as I did not!), and I wonder if he did it for the company as well as the break from so much brainwork. We always worked together on something, though I was a clumsy and unenthusiastic handyman. By 3:00 we were back inside to change, and then we worked at our desks until dinner at seven. Often, if Frances didn’t need any help with the meal, I cleared out and took a late walk along the cliff line. There was a path that followed the coast for miles. You could get right up to the edge and look down the red cliff face to the fallen boulders and the waves, which rolled big-headed, like sperm whales to the base. Geysers of whitewater marked the collisions, and retreating suds would gather and dissolve like the smoke rings of light in van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” And the wind was terrific, pushing me back, holding the crow-like choughs almost eye level, their wings quivering like beach kites. I would take a walk along the cliffs, and the setting sun would spread long light between Skomer and Skokholm, and sometimes the sheep would still be out, marking a path in the gorse with their wool, unthreatened by my presence.

Around seven I went back to set the table and help Frances organize the dishes, and when she was ready, I would ring the ship’s bell for John, and he would come up the hill in his sheepskin sweater and vest, and as we ate he brought us up to date on his work. We talked about other things too, but since the three of us focused all of our effort on his productivity, it was easiest to just talk about the work. Afterwards, John insisted on washing the dishes, but he allowed his study assistant to stand at his side and dry. He loved this chore too, he loved scrubbing the sink down when he was done and washing his hands up to the elbow like a surgeon. While we worked in the dark kitchen, I remember in those first days asking theological questions with an almost embarrassing zeal—about the pope, for example, and whether he was a universalist, and about John’s own beliefs regarding hell, which had landed him in some controversy among fellow evangelicals. John believed in a literal hell but not in eternal punishment. The consequences of not accepting Christ were eternal separation from God, but not conscious, writhing, Hieronymus Bosch suffering. Even granting the offense of humanity’s revolt against God, eternal conscious suffering seemed disproportionate, to John. This was a minority position among evangelical leaders, and it led someone in print to describe John as an “erstwhile evangelical,” which both baffled and hurt him deeply.

We washed and dried the dishes and put them away, then, back in the main kitchen, Frances got out an oversized bar of dark chocolate and broke off three individual squares. Chocolate was John’s guilty pleasure, and he always joked that the pudding at the end of our dinner had been wonderful but just a little bitter, and so didn’t we all need a piece of chocolate to compensate? But only a piece. We ate our small squares and withdrew to the sitting room to read until bedtime. If he was in a particularly good mood, or if we had guests, John liked to read aloud one of four Saki stories. As every study assistant knows, he read the same four stories over and over. Like the chocolate, it was a measured pleasure. Loving those four stories didn’t whet his appetite to start reading others. He had these four. It was genuine too, his love of those Saki stories. There were lines in those stories that released in John full, uninhibited laughter, including one in which a character sourly complains about tight boots. He roared with laughter at that. He had to set the book down.

When John didn’t read Saki aloud, we each read our individual books. In the damp parlor, on old furniture, with no television, we might have been in the 19th century. Our ancestors would have recognized us at once, rising early, working all day, sharing meals and insular routines, then winding down the day in stingy light. One winter, teased by the iron-gray ocean, I reread Moby-Dick and felt the Hookses as my own private Pequod. John occasionally read a classic like The Pickwick Papers. For a while Frances read about Antarctic exploration. And though he didn’t like to do this, and only succumbed a handful of times, I remember well the times John apologized and excused himself after dinner to have another go at something he was writing in his hermitage. Distracted or stuck, he needed to press on. He never did the opposite and take an afternoon off or drive along the coast to reboot or recharge. If he felt caught or stuck, he pushed harder, an impulse I internalized to my own peril later on. On these occasions, when I saw John go back down the hill for a final session of work, I understood it at once and was already in awe of it. Because on these days he would already have spent a good ten hours at his desk. He wrote from 6:30 to 7:50, 8:30 to 1:00, then 3:00-7:00. Never in those stretches, not one time in my four years, did he leave his study to take walks or brood. I did, though. Once on a Saturday morning, I took my camera and walked a long way down the cliff-line and back, and when I returned, I stood up on the headland where I could see into the hermitage, and I waited for John to look up so I could take his picture. I had to wait a long, long time. On another occasion, he and I were working at the Hookses without Frances, and because a church group was staying in the farmhouse, which they often did when we weren’t there, I worked in Frances’ office and slept in one of the outbuildings. It was winter, I remember, because when I slipped into John’s study with a cup of afternoon tea it was already dark outside. Leaning to his work, he didn’t turn around. I stood there a moment. The gas lamp wheezed, barely managing a candle’s light. The carriage clock flicked its cricket gears. I held John’s tea, and he didn’t notice I was there. Finally, I said, “Uncle, some tea.” He set his pen down and put his face in his hands. “I was miles away,” he said as he turned. His study windows were double-glazed. You could see but couldn’t hear the rough winter ocean. He could spend hours looking down at his pages without even noticing where he was.

Long before I arrived, he must have decided that utter discipline was the only way to complete what he wanted to do, which was to take in the abundance of the modern world and filter it through an ancient, biblical understanding of truth and authority. He was going to hold fast to evangelical truths but translate those truths to address contemporary dilemmas. His mentor told him one time early on that his preaching was like a solid house with sturdy walls but without windows. John became determined to let in air and light. He admitted he was much more formal in the early days, when everyone called him Rector and he wore a clerical collar. Third World travel changed him, exposure to cultures where Christ was loved without British inhibitions. I’m sure everyone who’s reading this knows all this about him, but it was powerful, nonetheless, to hear John confess it. He picked up the term “Uncle” and asked everyone to call him “Uncle John.” A child of the faded aristocracy, he learned to be comfortable with fraternal hugs. He even let himself hug Frances. John called the three of us his “happy triumvirate,” a term he borrowed from his hero, Charles Simeon.

After dinner, then, on ordinary nights, we would read in the little parlor, and around 9:30 Frances would put the kettle on for our hot water bottles, and we said a prayer together on our knees, often singing a psalm or reciting a collect, and then I did my last job of the day, which was to empty the stove’s ashes and fill it with fresh coal for the night. Outside, getting more coal from the shed, I, who am unsentimental about nature—too many mice in the kitchen, too many viruses in the air, too many eels in the pond!—even I felt overwhelmed below the spectacle of the night sky. Because we were tucked against the cliff face, unless a late tanker passed at the horizon on its way to or from the refineries, there was no artificial light anywhere. The stars had it all. It was a nomad’s night sky, with a thousand Stars of David. And they were so low, brooding on us, as it were, eavesdropping, some of them big as planets, Jupiter like a second moon. It was extraordinary, especially in winter. And I remember thinking, the universe isn’t enormous, it is close, part of what we are, and in the absence of other light, it was authoritative and majestic but also calm. Holding the coal hopper, I looked up until my neck burned, and with the binoculars John gave me as a welcoming gift, I could see four moons of Jupiter spaced in a line like bracelet beads, and on the moon when it was full the big crater facing earth with its sunburst of dust and the unreal boulevard of moonlight below on the waxy ocean. It was a universe easy to think of as being made by the biblical God. It wasn’t hard to intuit God there, silently supervising. In fact, it was impossible not to. When programmers aimed the Hubble Telescope at empty space, it showed back a teeming slide of older galaxies. That’s what the sky looked like at the Hookses. The same sky Abraham saw leaving Ur, the sky Ishmael observed from the crow’s nest of the Pequod, the blistering sky in van Gogh’s stormy mind. The experience of our ancestors—all of them—looking up to this same wide orchestra of light.

Toward the end of that first Hookses stay, John walked with me up to the cliffs one afternoon and then led me off the walking trail on a little goat path down the cliff face. It felt dangerous and thrilling: we were high above—directly above the coast, where the surf receded and returned in a kind of vacuumed roar, rinsing the boulders, filling the rocky gills with suds. There was a perch just under the cliff line, and we sat down there. The ocean was all around us, nibbling the late summer light. The shape of the perch protected us from wind. Sea gulls flew past at eye level—right there—and choughs with scarlet bills and matching scarlet legs so acrobatic in the gusts. To the left, the coastline followed more headlands, untouched by farms. To the right was the edge of Skomer Island, and in the distance the half-circle of Skokholm. John used to come here as a younger man, he explained, to think and pray, and even write. It was too difficult for him now, too physically demanding, but he wanted me to see it. And as we sat there that day for what could have been ten minutes but which I recall as long hours, he talked to me about my job and his vision for the church and what he felt God had called him to do and how we would work together and what he hoped for me—big picture things whose details don’t return to me as the moment itself does. We never did this again. I had no way of knowing at the time how rare and important this lone lingering hour or whatever it was would be. We just didn’t make room for stolen moments like these that were for their own sake, unrushed and without agenda. And I think it’s even possible John did enumerate some duties that afternoon, that this was like our other meetings would be in London, presenting my tasks, that he had rehearsed an agenda, but I don’t recall it that way. Maybe momentarily nostalgia relaxed him. He had been my age too, and as a younger man he would come up here to think and pray and write, and abide. I don’t know.

Toward the end of that first Hookses stay, John walked with me up to the cliffs one afternoon and then led me off the walking trail on a little goat path down the cliff face. It felt dangerous and thrilling: we were high above—directly above the coast, where the surf receded and returned in a kind of vacuumed roar, rinsing the boulders, filling the rocky gills with suds. There was a perch just under the cliff line, and we sat down there. The ocean was all around us, nibbling the late summer light. The shape of the perch protected us from wind. Sea gulls flew past at eye level—right there—and choughs with scarlet bills and matching scarlet legs so acrobatic in the gusts. To the left, the coastline followed more headlands, untouched by farms. To the right was the edge of Skomer Island, and in the distance the half-circle of Skokholm. John used to come here as a younger man, he explained, to think and pray, and even write. It was too difficult for him now, too physically demanding, but he wanted me to see it. And as we sat there that day for what could have been ten minutes but which I recall as long hours, he talked to me about my job and his vision for the church and what he felt God had called him to do and how we would work together and what he hoped for me—big picture things whose details don’t return to me as the moment itself does. We never did this again. I had no way of knowing at the time how rare and important this lone lingering hour or whatever it was would be. We just didn’t make room for stolen moments like these that were for their own sake, unrushed and without agenda. And I think it’s even possible John did enumerate some duties that afternoon, that this was like our other meetings would be in London, presenting my tasks, that he had rehearsed an agenda, but I don’t recall it that way. Maybe momentarily nostalgia relaxed him. He had been my age too, and as a younger man he would come up here to think and pray and write, and abide. I don’t know.

We sat with our knees up because that little nest was small, and the cliff boosted us dramatically over the ocean, somehow safe, and the spangled light on the sea offered mute tribute to the Creator. It was not a mystical moment, yet it was full. John and I sat there intuiting the same glorious purpose. I want you to know my mind, he had said. And there was nothing remotely burdensome about it, not here on the contemplative coast, not back in the farmhouse when we packed up to leave, not in the swarming heart of London, which I came to prefer and need and desperately crave whenever we returned to the isolation of the Hookses, which John always saw as a haven.

One final Hookses post card to close. We went back to Wales in December, this time for three weeks. One Sunday, in the early tea-time dark, John and I drove over to the neighbors’ farm to wish them Merry Christmas, and when we arrived the whole family, and some others, were out in the barn plucking geese they had just slaughtered for the butcher in Haverfordwest. Mrs. Bryan greeted us. She called out, not quite with alarm, “The vicar’s here,” and people acknowledged us but kept working. John and I stayed close by Mrs. Bryan as she pulled feathers from the dimpled gooseflesh and made small talk as she could. John smiled and said, “We’ve missed you at church, you know,” and I seized up a little on her behalf as Mrs. Bryan offered her excuse and kept at the feathers. When she turned the limp head of the goose back or to one side, you could see the little slit in the neck, not much more than a shaving cut, with a scar of dry blood. The smallest feathers floated around us without falling—confetti on the moon. In the cold barn, John asked after their only daughter, who was away studying agricultural sciences, and when the husband came over they chatted about the duchess, who owned their land, and they talked about the collies who had greeted us with some fury at the gate, and who I would watch with real awe the following year round up a herd of sheep and respond with absolute obedience and speed to a series of whistles from Mr. Bryan. The family never stopped working as we chatted. When John told them our own holiday plans, which involved flying to Africa, Mr. Bryan responded, “Bird-watching, then?” Because with the locals at church or on visits like this, we always talked birds.

We lingered our half hour in the barn, a vicar and his minder, and finally we went back to our car. The collies, having scouted us before, left us alone. John drove back across the airfield; I manned the big gates. Back at the Hookses, Frances waited with our tea. How was it? she asked. I started to tell her about the geese and the feathers and the collies. John spoke first: “You’d think they’d be more curious,” he said, “what I do up here three months of the year.”

—Todd Shy

(John’s Study Assistant, 1988-1992)