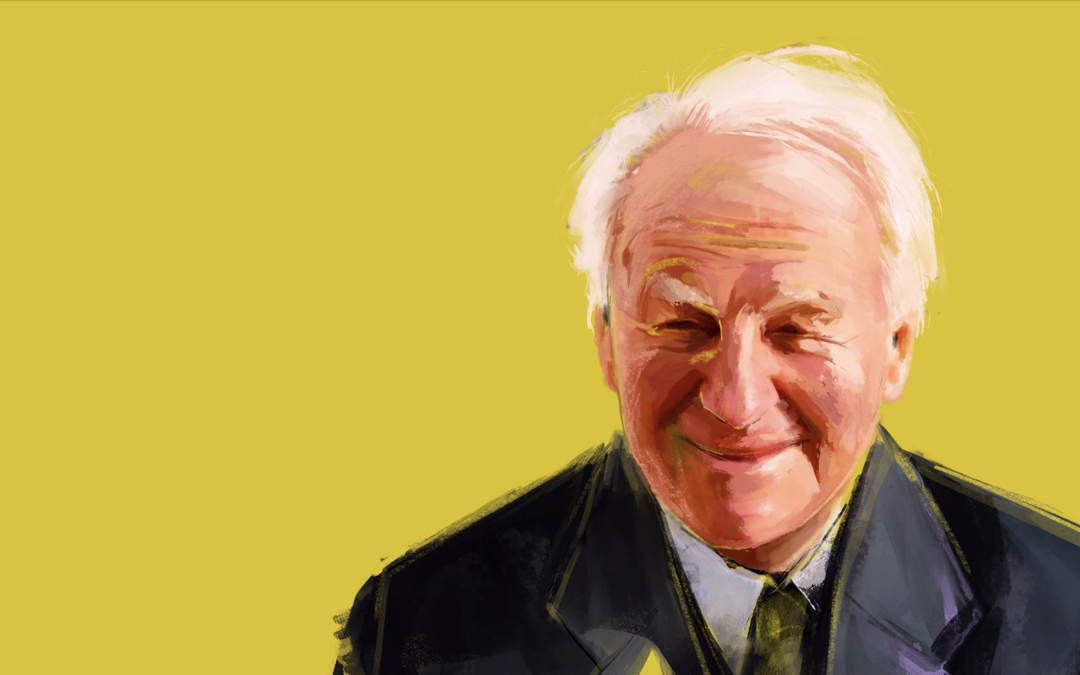

John Stott at 100: Why Evangelicals Still Need Him

By Russell Moore

The following excerpt comes from an article that first appeared on The Gospel Coalition, which supports the church by providing resources that are trusted and timely, winsome and wise, and centered on the gospel of Jesus Christ.

April 27 would be the 100th birthday of the late John R. W. Stott.

While many today might not know the name of this Anglican evangelical leader who towered over much of the 20th century, Stott deserves to be rediscovered because we just might need him now more than ever.

Lumping and Splitting

Stott, the longtime rector of All Souls Church, Langham Place, once lamented the evangelical tendency toward fragmentation by noting that biologists could be categorized as either “lumpers” or “splitters,” depending on whether they tended to group organisms into categories or to emphasize the differences between them. One might talk about the characteristics of birds, for instance, while another might get prickly about someone calling a mallard a duck. Stott wrote that the same often happens within the Christian community. Some emphasize similarities within the body of Christ, while others focus on the distinctive differences between Christian groups.

“Yet both processes become unhealthy if they are taken too far,” Stott counseled. “Some Christians go on everlastingly splitting until they find themselves no longer a church but a sect. They remind me of the preacher described by Tom Sawyer who ‘thinned the predestined elect down to a company so small as to hardly be worth the saving.’ Others lump everybody together indiscriminately until nobody is excluded.”

Stott’s influence endures because he refused to lump or to split except in ways that he found demanded by the gospel. If Stott’s primary objective had been his ecclesial career in the Church of England, he might well have sought unity that avoided such questions as the verbal inspiration of Scripture or the objective nature of the atonement, or the necessary historicity of the virgin birth and the bodily resurrection, much less the biblical teachings on such culturally contested questions as marriage and sexuality. But Stott often pointed out that, for him, “Anglican” was the adjective and not the noun. He was an Anglican Christian—and that meant his fidelity to Anglicanism was always subordinate to his fidelity to the mere Christianity of the gospel.

Stott’s Anglicanism

This sense of self and mission meant not only that Stott could, and did, speak to evangelical Christians in almost every denomination. Baptists learned to preach reading his book Between Two Worlds. Pentecostals defended the substitutionary nature of the atonement with The Cross of Christ. Presbyterians worked through the Sermon on the Mount with Stott’s commentaries. Missionaries of almost every conceivable evangelical tribe learned to articulate a missiology that holds together love of God and love of neighbor, faith in Christ and obedience to him, through Stott’s work with the Lausanne Covenant.

But it also meant that Stott could be a better Anglican. After all, if the Church of England were just a way to be a better Englishman, the English hardly need it anymore, apart from a royal wedding ceremony once or twice a decade and the upkeep of Westminster Abbey. This is the sort of church that philosopher Roger Scruton described as “my tribal religion—the religion of the English, who don’t believe a word of it.” But Stott—and his brother in arms J. I. Packer—were among those who saw their communion as not a cultural outpost but a way of expressing something much bigger than the English church, much bigger than England itself—the faith built on the Scriptures breathed out by God.

And so Stott’s Anglicanism—far from being the antiquated losing side in some bureaucratic tussles in Canterbury—is now represented in a vast and growing Anglicanism seen in Africa and Asia and in church plants in cities across North America. None of these is established by English culture—indeed, most would find it impossible to name more than one of Henry VIII’s wives. But they know the prophets and the apostles and the creeds and the liturgies and—above all—the gospel.

Stott’s evangelical conviction was deemed fundamentalist by some of his fellow churchmen, but sometimes in the world of evangelical Christianity—especially in America—he was suspect as “a squish.” After all, he would not split enough. Why was he still Anglican, they wondered, whether adjective or noun? Why did he not wade into the fiery debates over the meaning of the Millennium of Revelation 20? If he was Reformed—in the line of Cranmer—why would he not go beyond defending penal substitutionary atonement and demand a limited atonement too? Stott was one of global evangelicalism’s most thorough preachers of a Christian personal and social ethics, but, they asked, why wasn’t he at the forefront of the culture wars?

…

To read the rest of the article, visit The Gospel Coalition, where this article first appeared.

…

Russell Moore (MDiv, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary; PhD, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention and a Council member of The Gospel Coalition. He has written many books, including Onward: Engaging the Culture without Losing the Gospel (2015), The Storm-Tossed Family: How the Cross Reshapes the Home (2018), and The Courage to Stand: Facing Your Fear Without Losing Your Soul (2020). He and his wife, Maria, are the parents of five sons.